Autistic masking is when an autistic person hides or alters their natural responses in order to appear more neurotypical. In the past, some therapists, educators, and families may have explicitly taught masking behaviors in order to help the individuals that they work with “fit in” to the neurotypical world.

In recent years, however, Autistic adults have spoken out against this practice and research has been done highlighting the negative mental health effects of masking. It is time for us to alter our approach and start prioritizing our children’s mental health over making them appear neurotypical!

Masking can include behaviors like these:

- Forcing or faking eye contact during conversations

- Imitating smiles and other facial expressions

- Mimicking gestures

- Hiding or minimizing personal interests

- Developing a repertoire of rehearsed responses to questions

- Scripting conversations

- Pushing through intense sensory discomfort including loud noises

- Disguising stimming behaviors

People may mask Autism for a variety of reasons, such as:

- Feeling safe and avoiding stigma

- Avoiding mistreatment or bullying

- Succeeding at work

- Attracting a romantic partner

- Making friends and other social connections

- Fitting in or feeling a sense of belonging

Possible long-term outcomes include:

- Autistic Burnout and Exhaustion

- Anxiety

- Depression

- Frustration

- Decreased self-esteem

- Suicidal ideation

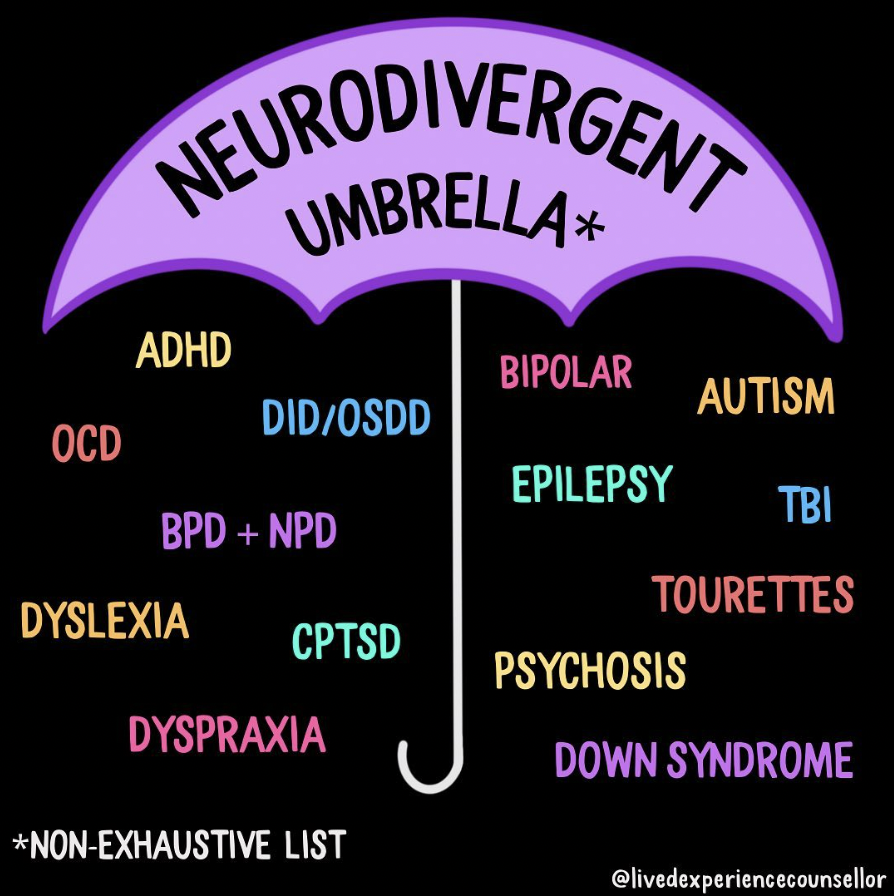

Masking is not limited to Autistic individuals!

Many people who fall within the neurodivergent umbrella (below) report negative effects of masking as well. This post will focus on Autistic Masking, however, due to the increase in research available on this topic.

What can we do to help?

- Never shame your child for stimming, scripting, avoiding eye contact, etc.

- Set up a sensory-friendly safe-space for your child where they can go after a long day to help “reset,” preventing Autistic burn-out.

- Teach your child self-advocacy skills. You can do this both by explicitly teaching them and by modeling use of self-advocacy for yourself.

- Ex: “I’ve had a long day, I need some time to myself in my safe space”

- Ex: “I flap my hands when I feel excited”

- Ex: “It is uncomfortable for me to make eye contact, but I am still listening to you”

- Provide resources that your child can use to assist with self-advocacy at times where they may have difficulty accessing spoken language, whether that be through use of visuals or other AAC.

- Have an open dialogue with your child about when they may want to mask and how they can support their mental health after choosing to mask. The reasons that Autistic individuals may choose to mask are multifaceted and may include a range of factors, including personal preference, context, systematic pressures, varying life experiences, and/or personal disadvantages.

- Ex: A gay, Autistic teenager may choose to mask in school because it is important to them to avoid bullying.

- Ex: A black, Autistic man may choose to mask around law enforcement in order to ensure their safety.

- Educate those who interact with your child (teachers, family members, etc.) about your child’s unique sensory, learning, and communication needs.

- Educate others about neurodiversity and how “different” does not equal “disordered.” Reducing the stigma against neurodiverse perspectives and actions is the best way that we can support neurodiversity long-term.

If you’re an Autistic adult, you may want to take this measure of masking to help you identify times that you may be consciously or unconsciously masking:

Blog by Laura Strenk, MS, CCC-SLP

Sources Used for this Blog Post:

- Healthline

- Compensatory strategies below the behavioural surface in autism: a qualitative study. The Lancet Psychiatry – VOLUME 6, ISSUE 9, P766-777, SEPTEMBER 01, 2019. Lucy Anne Livingston, MSc, Punit Shah, PhD, Prof Francesca Happé, PhD. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(19)30224-X

- “Putting on My Best Normal”: Social Camouflaging in Adults with Autism Spectrum Conditions. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. Laura Hull, K. V. Petrides, Carrie Allison, Paula Smith, Simon Baron-Cohen, Meng-Chuan Lai William Mandy. August 2017, Volume 47, Issue 8, pp 2519–2534 https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007%2Fs10803-017-3166-5

- Conceptualising compensation in neurodevelopmental disorders: Reflections from autism spectrum disorder. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews. Lucy Anne Livingston. Volume 80, September 2017, Pages 729-742 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neubiorev.2017.06.005

0 Comments