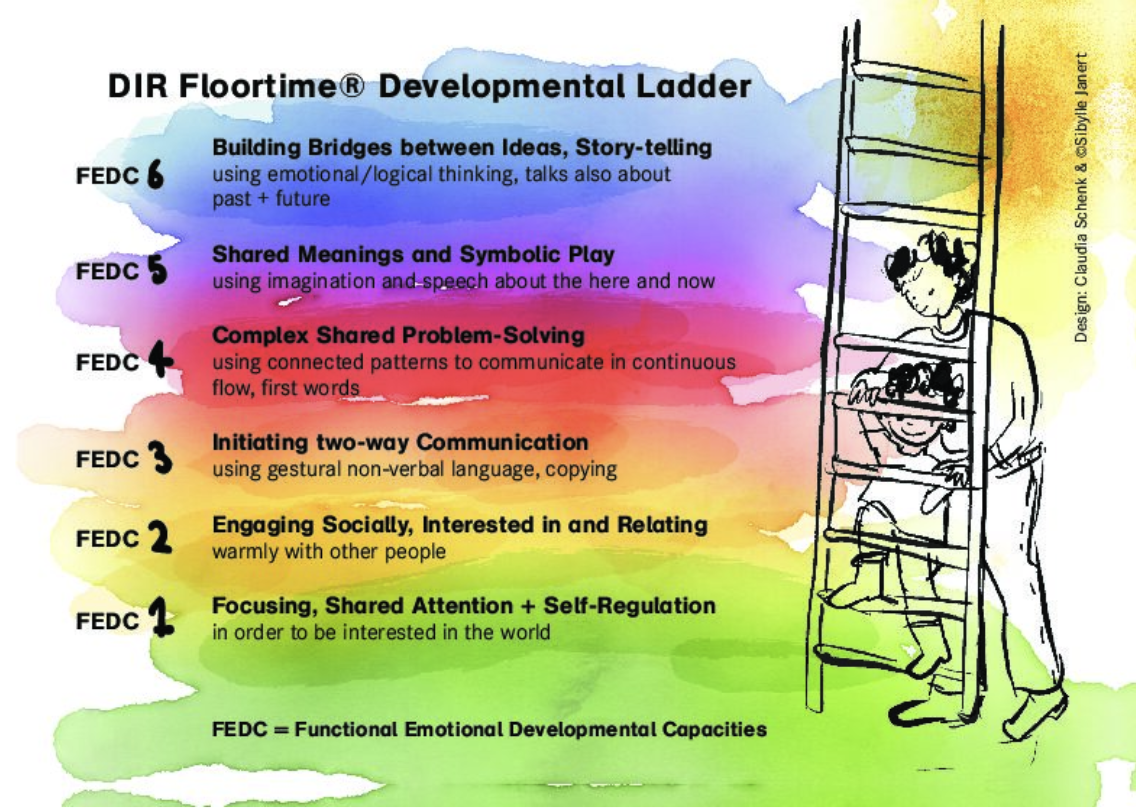

Being able to “play chess” is an important skill needed to not only target therapy goals at home, but also crucial for knowing when your child is ready to take on challenges. Using the principles of the DIR/Floortime approach, you can make observations about your child to assess when they are ready to receive demands. First, let’s look at the developmental ladder of play-based, DIR/Floortime intervention:

The photo above, designed by Claudia Schnenk and Sibylle Janert, nicely illustrates the developmental ladder of children with a DIR/Floortime lens. Each FEDC, Functional Emotional Developmental Capacity, compounds upon the one prior. In other words, FEDC Level 1, interest in the world, must be established prior to expecting consistent social engagement and interest in others, FEDC Level 2. When entering into a therapy session, I must always observe the child to determine which level they are at. If they enter the clinic with greetings and smiles, I can assume that FEDC Level 2 is established and I can jump to Level 3 to initiate two-way, purposeful communication with that child. Establishing that initial level is an important first step in knowing if your child is ready for something they perceive to be challenging, or non-preferred.

You’ve identified that initial level. Great! Now what?

Now, we start to play chess. It is expected for a child to move up and down this developmental ladder throughout a treatment session, just like it is expected for them to move around this ladder throughout the day. We can anticipate and plan given the information we know about the child. Does visual input overwhelm or distract the child? Let’s set them up for success and dim the lights and keep the play area as clean as possible. That way, when we place demands, after establishing FEDC Level 3 (e.g. purposeful two-way communication), we set the child up for success by removing a potential sensory barrier in advance to support motivation. Furthermore, knowing and planning play and communication with this perspective in mind will help you more quickly identify when your child is moving up or down the developmental ladder.

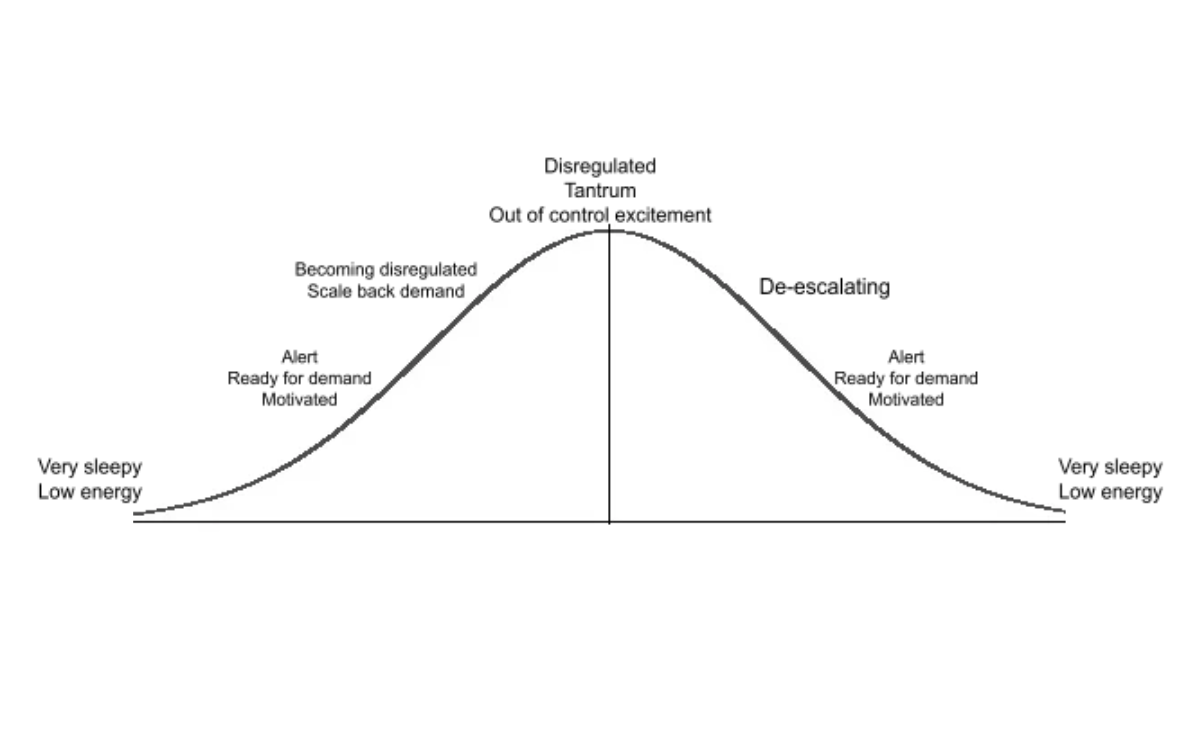

Another important consideration is discerning how to place and alter demands on your child based upon their emotional state. I think of emotions like a bell curve – the bottom of the bell curve is representative of feeling very tired or having low energy. The peak of the bell curve is representative of overstimulation or a tantrum. The “sweet spot” for learning, positive social engagement, and readiness for demands/challenge is about half-way up the bell curve, indicated on the graphic below. As a child’s emotional state begins to escalate beyond the sweet spot, be it positively or negatively (e.g. excitement or frustration), their ability to tolerate demands or challenges reduces. The closer a child is to the peak of the bell curve, the more we need to alter the demand, to then maintain engagement and motivation.

Let’s think about these concepts in a hypothetical situation.

I am playing with a child who has trouble with sharing and likes to maintain control of the toys, becoming upset and dysregulated quickly. Because I know this about the child, I will play my first chess piece: When introducing Legos, rather than giving them the box, I will give the child just one piece at a time to maintain control of the pieces and the activity. My next chess move is to establish motivation (e.g. FEDC Level 1) by passing the child 2-3 “free” pieces to ensure the child is motivated and invested in the activity without any demands (e.g. withholding pieces or requesting they say please/my turn). I would, instead, provide a language model to demonstrate how the language is used in real-time. This way, the child stays calm and is in a place where they can absorb the model provided, a.k.a. the sweet spot. If I were to place demands and withhold a Lego right away without motivation established, the odds of the child jumping up the bell curve to tantrum or dysregulation is much higher. The child would not be ready for demand to be placed. After giving 2-3 “free” Lego pieces, I would then place my first demand: maybe selecting a color from a group, using “I want” or “my turn” to request – whatever is appropriate for the child.

The goal in these first two chess moves is to establish and maintain engagement/rapport, regulation, and motivation. Those are the three key pieces needed to place increasingly challenging demands while maintaining buy-in. However, there is a chance the child is not ready for that new demand. I might notice some physiological signs that they are escalating up the bell curve like flushed skin, rapid breathing, whining, dilated pupils, and/or increased movement. I know that the child is much closer to the climax of my bell curve (e.g. tantrum, overwhelm) and I need to re-establish regulation, motivation, and attention by going down the developmental ladder to recover two-way purposeful communication. Rather than asking the child to say “I want the blue block” (which can feel very overwhelming due to sentence length or withholding too long), I can reduce the demand to “I want block,” reduce further to “want,” and if verbal imitation is too demanding, reduce even further to pointing or giving a high five. Even though the original target was not imitated, I still maintained control of the activity by having the child complete a request for me before receiving the reward. This reinforces enduring non-preferred tasks in order to get what’s preferred. With practice, the child will learn my expectations and understand that if they complete the work, they will receive their reward. Over time the child will be able to tolerate longer periods of work (e.g. demand, challenge) before their reward. Their endurace for non-preferred activity will increase.

Everytime you think about placing demands, your child may present differently. It can be challenging to continually play chess to unlock your child’s potential. Good news is, this strategy can be practiced in all kinds of situations: playtime, mealtime, running errands, and morning routines to name a few. Just like chess, these strategies are not meant to be learned and mastered quickly. They are mastered over time with consistent use. It’s an evolving skill that changes with each iteration, just like a chess game. When you can establish, increase, and reduce demands to rise up the developmental ladder, you’ve gotten a checkmate.

0 Comments